Why We Need an LGBTQ Museum

I’ve recently been very honored to join the advisory committee for a new not-for-profit organization, The Lavender Effect. The mission of The Lavender Effect is “to celebrate our heritage and inspire future generations” and the organization is “committed to creating a state-of-the-art LGBTQ Museum and Cultural Center that will be among the foremost educational and entertainment institutions in Southern California.” I’m thrilled to be working at the genesis of such an important project.

Since its official announcement on June 1, 2012, I’ve seen and heard various responses to the exisitence the organization, but a common question that keeps coming up is “Why do we need an LGBTQ Museum?” While The Lavender Effect as an organization has its own answers to this question, I wanted to memorialize my answers here on my site, now, at the beginning of this process, to address this issue from a personal viewpoint.

Since its official announcement on June 1, 2012, I’ve seen and heard various responses to the exisitence the organization, but a common question that keeps coming up is “Why do we need an LGBTQ Museum?” While The Lavender Effect as an organization has its own answers to this question, I wanted to memorialize my answers here on my site, now, at the beginning of this process, to address this issue from a personal viewpoint.

We need to present our culture

What The Lavender Effect is proposing is more than just a simple museum; the project will produce an LGBTQ museum and cultural center. This is a key distinction. A museum, as it is commonly thought of, is an archive of the past. Museums are stuffy. Static. Dead. They contain frozen snapshots in time. Now, of course, this is not true of all museums, but it is not a completely inaccurate generalization. The Lavender Effect’s Museum and Cultural Center strives to be a hub of current cultural activity. The exhibits will be highly immersive and interactive (my area of advisement), educating and entertaining visitors as they travel through. Gay history, especially Southern California gay history, is being written every day, so the museum will operate not only to preserve our past, but capture our present for future generations. A coffee shop, bookstore, and performing arts spaces will all lend to maintaining a living, growing culture — day in, day out.

We also need to show our history to the world at large, not just for our own community. Like other cultural and heritage museums (e.g., the Japanese American National Museum, the Museum of Tolerance, and the Autry Western Heritage Museum), The Lavender Effect will be for all people, straight as well as LGBTQ. Too often someone from outside a sub-community can not understand what it can be like to be marginalized or discriminated against or even live daily life as a member of that sub-community. By having a broad, inclusive, open museum, we can share our struggles, triumphs and tragedies with everyone and increase the levels of tolerance and understanding.

We need to preserve our culture

After the recent Los Angeles Pride celebration, a posting on a friend’s Facebook wall lamented on how many young (and not so young) LGBTQ people did not know that PRIDE was originally an acronym for Personal Rights in Defense and Education. He went on to explain that PRIDE was founded in Los Angeles three years before Stonewall and was one of the first gay groups to take to the streets and protest in the face of police and status quo opposition. I admitted in the comments that even I didn’t know about this (and I’ve made a concerted effort to educate myself on gay rights history).

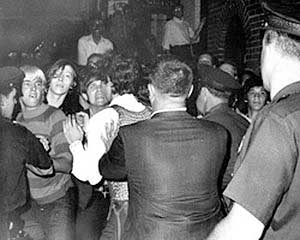

I also pointed out in those comments that I’ve even had to educate young gay men and women on the Stonewall Riots (which would seem to be commonly known in the gay community if for no other reason than the first Pride parades and festivals were scheduled (and are still scheduled) to celebrate its anniversary). The first protest that PRIDE formed was in response to a New Year’s Eve raid at the Black Cat Tavern in Silverlake, across the street from the now uber-trendy Intelligentsia Coffee, yet this significant location in our history is lost on most of the local residents, let alone the world at large.

I also pointed out in those comments that I’ve even had to educate young gay men and women on the Stonewall Riots (which would seem to be commonly known in the gay community if for no other reason than the first Pride parades and festivals were scheduled (and are still scheduled) to celebrate its anniversary). The first protest that PRIDE formed was in response to a New Year’s Eve raid at the Black Cat Tavern in Silverlake, across the street from the now uber-trendy Intelligentsia Coffee, yet this significant location in our history is lost on most of the local residents, let alone the world at large.

The bottom line here is that this history is less than 50 years old and we’re forgetting it. We’re letting it slip through our fingers and we’re not educating ourselves as a community about the fights and struggles that we’ve had to endure because, ironically, we’ve gained greater acceptance into society-at-large as a result and we no longer feel the daily struggle. Even so, and just as we still teach about the American Revolution in history classes, we shouldn’t forget these hard fought battles that have earned us such gains. Many of the earliest founders of gay rights organizations are no longer with us and we should do everything we can to preserve the stories of the ones who are still here while we can.

We need to pass on our culture

I’m Italian-American by birth, certainly by heritage and, many would say, by culture as well. I know about Italian-American history and traditions because I grew up learning about them and my relatives told me stories about them. I know where my family comes from in Italy and Sicily. I know when they arrived in Ellis Island. I know where they first lived in the U.S. I know why we eat the Feast of the Seven Fishes on Christmas Eve. I know what a “Football Wedding” is. I know why we revere Frank Sinatra and why we dislike stereotypes like mobsters and Mario Bros. As Lynn Ahrens wrote in Schoolhouse Rock’s “The Great American Melting Pot”

Go on and ask your grandma

hear what she has to tell.

How great to be American

and something else as well.

The Eurocentricity of that song aside, it’s very telling about how we, as Americans, pass on our culture, customs, history and heritage. We do it through generational and family ties. Well, for gay Americans, we usually don’t have that family connection. In fact, for many of us, we hide our homosexuality from our families until our teen years or later (I didn’t come out to myself until my early 20s and to my family until my mid-20s) and then we become the teachers to the rest of our immediate family. How are we then to learn of our gay history and culture in the first place?

The Eurocentricity of that song aside, it’s very telling about how we, as Americans, pass on our culture, customs, history and heritage. We do it through generational and family ties. Well, for gay Americans, we usually don’t have that family connection. In fact, for many of us, we hide our homosexuality from our families until our teen years or later (I didn’t come out to myself until my early 20s and to my family until my mid-20s) and then we become the teachers to the rest of our immediate family. How are we then to learn of our gay history and culture in the first place?

For many of us who came out pre-Internet, we were lucky to have older mentors who welcomed us into the gay community (and this was usually done in gay bars, so the beginnings of this personal education didn’t even start until after age 21). Some were not as lucky and had to find their own way and their own identity as they came out. Even then, the oral histories of the gay community were spotty, incomplete and editorialized. For the particularly curious or those who enter the academic field of “Queer Studies” (wow, is it even still called that?) there are many books and publications that deal with gay history, but for the average gay person, this information is not sought out. Additionally, since gay culture (following the trend of American culture in general) is increasingly youth oriented, young gays and lesbians are too often focused on their present and shun their older peers who might help as mentors and educators of the community.

As LGBTQ Americans, we lack a vital resource in the casual transfer of cultural and historical knowledge from one generation to the next, even intergenerationally. We form our own families, but we aren’t raised in these new families and so we don’t have years to gather their knowledge and wisdom as we do in our genetic families. An LGBTQ Museum allows us to hear their stories from the past, tell our stories of the present and write new stories for the future.

Michael, thank you for your excellent assessment. I too am on the Advisory Board for TLE, and I could not be more excited about this project!

Well said, Michael. I’m peripherally involved in this project via Ivy Bottini, so am aware of the efforts being put into it to be meaningful, authentic and a valuable resource to many who come down the pike. You captured that energy well. I’m very excited this is happening!

Thank you, Dottie and Ken! Not only am I very excited to be working on this project as well, but I’m so glad that my reasons for wanting to get involved are share by so many like-minded folks!

Hi Michael, thanks for he article, and I look forward to meeting you. Also wanted to share a couple of thoughts. Something important about good museums is that they serve as a portal to the road traveled to arrive at what is current. It’s all too common to think that how things are now is how they always were, and that’s a shame. Also, unlike our genetic/cultural heritage, much of our history and contributions to civilization have been *repressed*, and that’s a tragedy.